From Robert Grosseteste to Jean-Francois Lyotard, Augustine s advice that point is a dilation of the soul ("distentio animi") has been taken up as a seminal and debatable time-concept, but in "The area of Time," David van Dusen argues that this dilation has been essentially misinterpreted. Time in "Confessions" XI is a dilation of the "senses" in beasts, as in people. And Augustine s time-concept in "Confessions" XI isn't Platonic yet in schematic phrases, Epicurean. choosing new impacts at the "Confessions" from Aristoxenus to Lucretius whereas protecting Augustine s phenomenological interpreters in view, "The house of Time" is a path-breaking paintings on "Confessions" X to XII and a ranging contribution to the historical past of the concept that of time."

Read or Download The Space of Time: A Sensualist Interpretation of Time in Augustine, Confessions X to XII (Supplements to the Study of Time) PDF

Best Classical Studies books

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Greek Religion (Oxford Handbooks)

This instruction manual deals a accomplished review of scholarship in historic Greek faith, from the Archaic to the Hellenistic sessions. It offers not just key info, but additionally explores the ways that such details is collected and different ways that experience formed the world. In doing so, the quantity offers a very important learn and orientation device for college kids of the traditional global, and in addition makes a necessary contribution to the most important debates surrounding the conceptualization of old Greek faith.

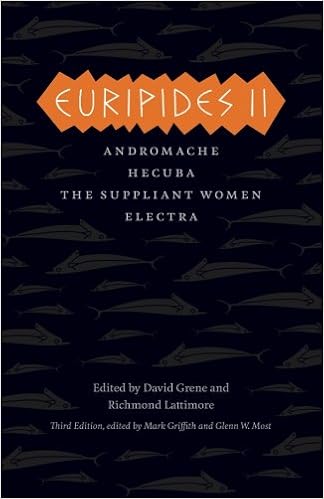

Euripides II: Andromache, Hecuba, The Suppliant Women, Electra (The Complete Greek Tragedies)

Euripides II includes the performs “Andromache,” translated through Deborah Roberts; “Hecuba,” translated by way of William Arrowsmith; “The Suppliant Women,” translated by means of Frank William Jones; and “Electra,” translated through Emily Townsend Vermeule. Sixty years in the past, the collage of Chicago Press undertook a momentous venture: a brand new translation of the Greek tragedies that may be the final word source for lecturers, scholars, and readers.

Euripides I: Alcestis, Medea, The Children of Heracles, Hippolytus (The Complete Greek Tragedies)

Euripides I includes the performs “Alcestis,” translated by way of Richmond Lattimore; “Medea,” translated by way of Oliver Taplin; “The young children of Heracles,” translated via Mark Griffith; and “Hippolytus,” translated by means of David Grene. Sixty years in the past, the college of Chicago Press undertook a momentous venture: a brand new translation of the Greek tragedies that may be the last word source for academics, scholars, and readers.

Euripides IV: Helen, The Phoenician Women, Orestes (The Complete Greek Tragedies)

Euripides IV includes the performs “Helen,” translated through Richmond Lattimore; “The Phoenician Women,” translated by way of Elizabeth Wyckoff; and “Orestes,” translated through William Arrowsmith. Sixty years in the past, the college of Chicago Press undertook a momentous venture: a brand new translation of the Greek tragedies that might be the final word source for lecturers, scholars, and readers.

Additional resources for The Space of Time: A Sensualist Interpretation of Time in Augustine, Confessions X to XII (Supplements to the Study of Time)

15. 22)— but this can be a strictly damaging echo. The hyper-heavenly’s contemplatio isn't contuitus, and therefore, its delectatio isn't really distentio. (Recall the prolonged dialogue of Confessions XI. 31. forty-one in bankruptcy five. ) The inexplicit justification for this negation in ebook XII is itself duplex, but converges—I contend—on the flesh: (α) in contrast to human cogitatio, that is rooted in and incommutably directed in the direction of the novel mutivity of contuitus (≈ senseperception), and hence is distentio—‘distentio sensuum’ as a ‘distentio animi’—the hyper-heavenly’s contemplatio is speculatively rooted in and immutably directed in the direction of a mindless and static eternity; and sixty four And cf. Aug. Conf. XIII. three. 4: . . . non existendo sed intuendo inluminantem lucem eique cohaerendo, ut et quod utcumque vivit et quod beate vivit non deberet nisi gratiae tuae, conversa in line with commutationem meliorem advert identity quod neque in melius neque in deterius mutari potest. 166 bankruptcy 7 (β) in contrast to human voluptas, that is originarily considering and derived from the flesh (≈ sensation, acquisition),65 and hence has spatial intentio and temporal distentio as its co-conditions,66 the hyperheavenly’s rapture on the divine unicity is speculatively conceived as detached. In essence: the speculative haerere of the caelum intellectuale to Augustine’s deity, which ends up in its timelessness, is negatively derived from and mirrors a sub-phenomenal haerere of anima-animus to the flesh, which haerere (≈ vita) in Confessions X is the precondition for temporal distentio in Confessions XI. that's, the contemplatio and delectatio of the caelum intellectuale—its ‘cohesion’ to the deity—negatively formalize, when it comes to the method i've got indicated during this bankruptcy, the sense-affective structure of spatial purpose and temporal dilation when it comes to what I name an ‘inhesion of the flesh. ’ For Augustine, it truly is this ‘inhesion of the flesh’ through a soul which possibilizes a sense-affective ‘dilation’ in areas and occasions. yet this, in fact, has to be verified. 7. four extra on Augustine’s Root-Verb Haerere It suffices to watch, in the beginning, human, temporal haerere is orientated to god at Confessions X. 6. 8—the passage quoted above—and that this mysticological ‘clinging’ has precedents in Confessions I to IX. sixty seven that's, the haerere which turns into a technical time period in ebook XII, and is basically associated with 65 Aug. Conf. I. 6. 7: nam tunc sugere noram et adquiescere delectationibus, flere autem offensiones carnis meae, nihil amplius. 66 Aug. Conf. I. 6. eight: et ecce paulatim sentiebam ubi essem, et voluntates meas volebam ostendere eis in keeping with quos implerentur, et non poteram, quia illae intus erant, foris autem illi, nec ullo suo sensu valebant introire in animam meam. sixty seven Augustine will gloss Conf. X. 6. eight at X. 17. 26: ecce ego ascendens in step with animum meum advert te . . . volens te attingere unde attingi potes, et inhaerere tibi unde inhaereri tibi potest. Cf. additionally Conf. I. nine. 15: estne quisquam, domine, tam magnus animus, praegrandi affectu tibi cohaerens, estne, inquam, quisquam (facit enim hoc quaedam etiam stoliditas: est ergo), qui tibi pie cohaerendo ita sit down affectus granditer; IV.